Bill Eppridge - History in the Making

January 13, 2011 | Source: Monroe Gallery of Photography

Bill Eppridge - History in the Making

DOUBLE EXPOSURE

By Lynne Eodice

Jan 11, 2011

All photos by Bill Eppridge.

In a notable career shooting primarily for Life and Sports Illustrated, Bill Eppridge has covered wars, political campaigns, heroin addiction, the arrival of the Beatles in the United States, the summer and winter Olympics, and perhaps the most dramatic moment of his career--the assassination of Senator Robert Kennedy in Los Angeles. His photography has won numerous awards and has appeared in traveling exhibits throughout the world. He has taught photojournalism at Yale University, the Missouri Photojournalism Workshop, Barnstorm: The Eddie Adams Workshop, Rich Clarkson's Photography at the Summit, and Sportsshooter Workshop.

When his family lived in Richmond, Virginia at the end of WWII, a man with a pony came to the Eppridge household one day and offered his photographic services. Bill Eppridge, who was about 10 at the time, got out his Brownie Starflash 620 camera and posed with it. "I started thinking, 'this guy doesn't have a bad job. He gets to travel, meets some interesting people and he's even got a pony.'" As a young boy, he waited for the mailman to deliver Life magazine every week, and always enjoyed the photographs by David Douglas Duncan, Robert Capa, and Henri Cartier-Bresson. "I was fascinated by this work and I felt that it affected the people who looked at these pictures." He was also moved by Joe Rosenthal's image of the flag being raised at Iwo Jima. "Over the years, I thought there was some power with this medium. If you can do a couple of good things for people in your life, then you've lived a good life," he remarks.

Joining the Ranks of his Heroes

After graduating from high school, Eppridge decided he wanted to be an archaeologist and attended the University of Toronto. He also took pictures for the Varsity, the campus newspaper. "By the end of my second year there, I was Director of Photography," he remembers. His grades in school began to slip, and he realized that photography was really where he wanted to be. One of the faculty members at the college advised him to go to the University of Missouri, as it was the best school for journalism.

Ethel Kennedy Leans Over Robert F. Kennedy As He Lies Wounded on Floor of Ambassador Hotel Kitchen, June, 1968 © Time

Twice, he won the National College Picture Competition sponsored by the National Press Photographers' Association (NPPA) and the University of Missouri. "In both cases, the first prize was an Encyclopedia Britannica and a week's internship at Life magazine," Eppridge says. "During those weeks, I met some of the people whose pictures I had seen as a child." One of his winning images was the result of a lucky accident, taken when a Columbia, Missouri newspaper needed a cover for its farm supplement. Eppridge agreed to take pictures of an impending tornadic storm, and pulled his car up alongside a farm just as the sky was turning black. A farm horse, which he describes as "an old plug," approached him. Eppridge slipped, making a sudden move that startled the horse, and it ran away. Shooting quickly, he got one dramatic picture of this off-white horse galloping against a dark, foreboding sky. "The old plug looked just like a thoroughbred," he relates. The image, titled, 'Stormy,' also won first place Pictorial in the NPPA's Pictures of The Year competition-- Eppridge credits it with starting his career. (And fortunately, the horse was fine, as the storm never really touched down.)

He says, "Most of the Missouri grads at the time migrated to National Geographic." Thus, he made inroads at both NGS and Life. His first assignment for NGS was a nine-month trip around the world with the International School of America. The trek started in Japan and moved across the continents to Europe. "I didn't attend classes like they did, so I was free to roam. It was a great way to get introduced to this profession and to the world outside," he recalls.

A Ground Floor Opportunity

He moved on to Life following the advice of his Picture Editor at NGS, Bill Garrett, who was also a graduate of Missouri. "He was a brilliant man," exclaims Eppridge, "who always had a very good sense of what was going on in the world." NGS had wanted Eppridge to remain in Washington while they laid the story out, and put him to work in the magazine's color lab as a technician. Once the story was laid out, the editor, Melville Bell Grosvenor wanted to make him a staff photographer. "I felt really wonderful about this," he says. "But a few days later, Garrett told me, 'you've got to get out of here. They want you on staff and you can't do that.'" Garrett told the young man that the world was, in essence, starting to "blow up," with unrest in Latin America and Southeast Asia. "You've got to photograph those places," he advised Eppridge. "You won't get a chance to do that if you stay here."

One of the judges of a picture competition that Eppridge had won was Roy Rowan, the Life Bureau Chief in Chicago. "I went to New York blindly with a portfolio under my arm," Eppridge says. "I didn't make any phone calls and didn't set anything up." He thought Life was a little out of reach, but hoped to get a free lunch from one of his friends there. "I went over to the Time-Life building and was standing at the corner of 51st and 6th Avenue. This voice behind me says, 'Eppridge, is that you?' and I turned around and said, 'Roy Rowan, is that you?'" As it turned out, Rowan was the new Director of Photography at Life, and told Eppridge they were looking for young photographers. He had an opportunity to start shooting for the magazine that afternoon, but since he hadn't brought his camera with him, he began his career with the venerable publication after moving to New York several weeks later. "The first assignment I shot ran in the magazine, and so did the next several stories," he says--an impressive feat, considering that Life had a very high "kill factor" at the time. Soon Life made Eppridge a staff photographer.

His assignments with the magazine marked some very important points in history, beginning with coverage of several wars in the early sixties. "I went to Panama, Santa Domingo, and Managua for those revolutions," Eppridge notes. "I spent some time in Mississippi when the bodies of three slain civil rights workers were found, and I was in Vietnam. It taught me that war ain't glorious at all--not made for human consumption." He also did a story on heroin addiction, where he lived with a pair of addicts in New York City for about three months, in an area known as Needle Park. "They were just being themselves because that's the way I work," he says. "I prefer to be a speck on the wall." The resulting story won several awards, including the National Headliners Award that year. It was also the inspiration for Al Pacino's first film, "Panic in Needle Park."

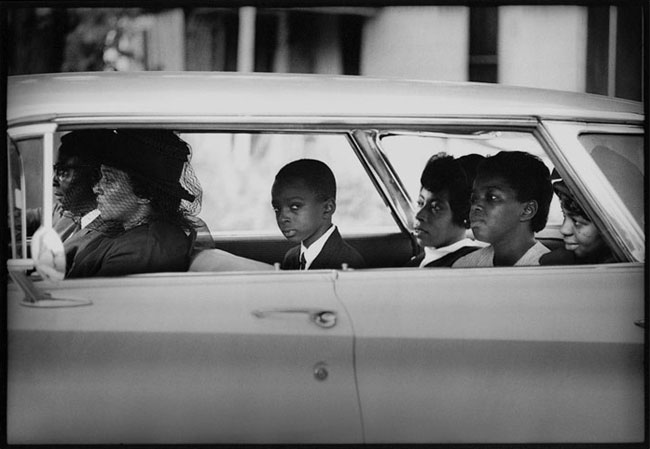

All in all, he's covered a wide range of stories for Life, including spending a week with Jonas Salk, the inventor of the Polio vaccine. He photographed the summer Olympics in Mexico, and spent time with Dick Butkus during his rookie year with the Chicago Bears. He was also the first photojournalist to be allowed to travel on tour with Lyndon B. Johnson during his presidency. "I was on Air Force One for several days," he comments. Eppridge also covered civil rights issues, and was with the family of James Chaney after his body was found, and photographed his funeral. "I was able to show how that family dealt with a terrible event."

Rock n' Roll History

In 1964, the magazine sent him on assignment on what would become a legendary rock band's historic arrival to the U.S. "One morning my boss said, 'Look, we've got a bunch of British musicians coming into town. They're called the Beatles.'" Eppridge, who wasn't really a rock n' roll fan, recalled that Life had recently done a story about a phenomenon known as Beatlemania--"The Beatles were running down the street with little girls screaming and running after them." His orders were to cover their arrival in New York from a unique vantage point where nobody else happened to be, so Eppridge went to JFK International Airport to scout out locations. "I wandered around and found a spot that I liked," he says. "So I set up there, leaned against a pole, and waited." Before long, another photographer headed in his direction, apparently also seeking a good location, and set his camera bag down about 20 feet from Eppridge. He made acquaintance with this photographer, who turned out to be the Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist Eddie Adams, on assignment from Associated Press.

"I decided I liked the guy, although he was competition," says Eppridge of that initial meeting. They discussed where the ideal spot would be to shoot the British group's arrival, and both concluded that it would be best to be on the plane, behind the Beatles as they came out the door, photographing them and the huge, uproarious crowd below. When the plane landed, the door opened, "and out came this beautiful Pan Am stewardess, followed by the Beatles, who were dressed like proper young men," he remembers. And lo and behold, a photographer followed them out the door of the plane. "Eddie and I just looked at each other," Eppridge says. It turned out that the photographer was Harry Benson, who was working for one of the British newspapers at the time.

Eppridge covered the first few days that the Beatles were in New York, and learned a lot about music. "These were four very fine young gentlemen, and great fun to be around," he says. After he introduced himself to Ringo, who consulted with John, the group asked what he wanted them to do while being photographed for Life. "I'm not going to ask you to do a thing," was Eppridge's reply. "I just want to be there." He was invited to come up to their hotel room and "stick with them." The resulting photos from this story were on display at the Smithsonian for an entire year. That exhibit is still traveling and is currently in Liverpool, England.

A Pivotal Moment in Time

In 1966, he was assigned to cover Bobby Kennedy's political campaigns. "He endorsed candidates who had helped his brother," notes Eppridge. "But he was also testing the waters to see how his own candidacy would go over in '68." That year, Life asked him to cover Kennedy's campaign, beginning with the primaries. At that time, the magazine assigned one staffer to each major candidate. On June 5, 1968, at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, he was instructed by his boss to "stay as close as you can to Bobby. The editors here feel that if he wins California--which appears likely--he will probably be the next President of the United States." Back then, he says, you could do all your dealings directly with the candidate, no middleman involved. As opposed to the massive security today, Bobby Kennedy only had one bodyguard, Bill Barry.

Kennedy assured Eppridge that he would be part of his immediate group, which meant that wherever the Democratic candidate went, Eppridge wouldn't be far behind. "When he came off the stage, we would form an arrowhead-shaped wedge of photographers who would go through a crowd," he relates. "If people got pushed out of the way, then it was the press who did it and not the candidate." Being in the "pocket" of the wedge also gave Senator Kennedy freedom to move around and shake hands. "We had that wedge formed at Barry's direction to go out of a different exit," he says. "Bobby came off the stage, and came down to Barry, who said 'Senator, this way,' pointing across the room." But Bobby insisted on going out through the kitchen, which was the way they had entered. Again, Barry told him to go across the room, but the Senator refused, turned, and entered the kitchen.

"We couldn't scramble fast enough," Eppridge remembers. "We all headed towards the kitchen, but were behind him about 15 feet." As he tried to catch up, he went through the kitchen doors, and heard the sound of gunshots. It was eight shots. Thinking quickly, he grabbed the television cameraman and shoved him forward to utilize his light. Among the thoughts Eppridge had at that moment was a very loud and clear one: "You are not just a photojournalist, you're a historian."

Juan Romero, a busboy with whom Kennedy had been shaking hands, now cradled the Senator's head in his arms. Eppridge had time to capture only a few frames. "The first one was out of focus," he says. "In the second one, Romero is looking down at Kennedy, and in the third one, Romero was looking up with a pleading look." After that, the scene became bedlam. "You think you're in a position to help," he muses. "There were doctors in the room, and I knew I could only do my job because there was nothing I could do to help the Senator. So I just concentrated on doing my job."

Eppridge has published two photographic books on Bobby Kennedy. The first, titled The Last Campaign, was published in 1993 on the 25th anniversary of Senator Kennedy's death. The most recent one is entitled A Time It Was: Bobby Kennedy In The Sixties, (Abrams, June 2008) and includes never-before-published color photographs from the campaign that had been lost for 40 years. "What I would like people to know about is the freedom we (photographers) had and the ability we were given to tell the truth," Eppridge comments. "The press is controlled in such a way today that you almost never see the real person you're photographing. You're taking pictures of what their handlers want you to see."

Protecting Natural Resources

"After Bobby was killed, of course, I didn't do any more politics," he says. Instead, he took on more outdoor assignments; hunting, fishing, and environmental photography. Before they folded, Life let a lot of photographers go, but kept Eppridge. When the magazine ceased publication in December 1972, he moved on to Sports Illustrated, where he is still on the masthead. "I liked SI because they were doing the types of stories I enjoyed," he says. The publication sent him to Africa to do a story on poaching, which he describes as "interestingly scary." He's also covered six America's Cup competitions and five Winter Olympics. "The best-run games were in Sarajevo," Eppridge observes. "That was before the war destroyed that country." He describes his work with SI as "Sports with no balls," as he's no longer fond of shooting baseball, basketball, or football. "I prefer to do something that I've never done before," he remarks. "Rather than specialize, I'm a generalist."

When asked about advice for photographers starting out today, Eppridge emphasizes telling the truth. "I believe our world is at a time right now in which it should be documented completely." He says we should all be protectors of our environment and heritage. "If we can influence people with photographs, maybe we'll be able to maintain our planet."

See Bill Eppridge's historic photographs at Booth A-102 during Photo LA, January 13 - 17, 2011,.