"The function and mission of photography is to explain man to man and man to himself"

July 6, 2013 | Source: Monroe Gallery of Photography

Double exposure: photography's biggest ever show comes back to life

The Family of Man, a groundbreaking post-war exhibition seen by more than 10 million people, reopens in Luxembourg

Giovanna Dunmall

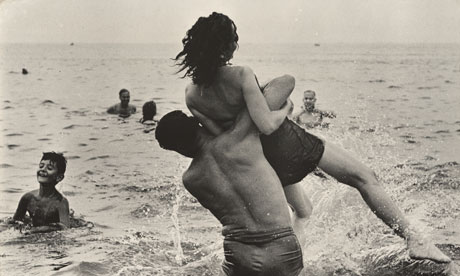

"Family of Man changed the way we view photographs today, and how we think about exhibitions," says Anke Reitz, conservator of The Family of Man in Luxembourg, where the collection has been since 1994. "It is a milestone in the history of photography." Steichen chose images grouped by themes intended to be so universal that anyone in any culture could identify with them: birth, fathers and sons, mothers and children, education, love, work, death and religion. The images were hung in particular formations, some dangling from wires overhead or attached to poles. The birth photos were arranged inside an intimate circular structure, while theatrical lighting created further drama and atmosphere. Steichen hung the photos without captions. "The exhibition was meant to be understood around the world without the need for words," says Reitz.

Alfred Eisenstaedt's image of a University of Michigan marching band drum major practising his high-kicking prance, followed by admirers in Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1950

Alfred Eisenstaedt's image of a University of Michigan marching band drum major practising his high-kicking prance, followed by admirers in Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1950  American anthropology, Leon Levinstein, Couple in New York, 1952 Photograph: Howard Greenberg Gallery/Leon Levinstein

American anthropology, Leon Levinstein, Couple in New York, 1952 Photograph: Howard Greenberg Gallery/Leon Levinstein Sections of the show are now dated and gendered, and there is no doubt that the main worldview being expounded was white, western and male. One theme, "household and office work", shows only women cooking and cleaning, while the predominance of the nuclear family in many photographs, themes and arrangements feels reactionary and simplistic (as if the family could conquer all - even issues such as racism or social inequality).

For Reitz, such criticisms are founded, but are "part of the history of the exhibition". The Family of Man is very much a product of its time and its creator, she says. As a contemporary viewer, it is hard to appreciate quite what an impact this anthropological photographic survey must have had, nearrly 60 years ago, when viewed in places as culturally diverse as Indonesia, Russia, Japan, Italy and Laos. "For many people, it was like seeing the world for the first time," says Reitz. "A lot of them didn't have TVs or access to magazines."

A world revealed, Peruvian Flute Player, Pisac, Peru, 1954, by Eugene Harris

A world revealed, Peruvian Flute Player, Pisac, Peru, 1954, by Eugene Harris The Family of Man has stood the test of time because of how innovative Steichen was as a curator. He displayed photos without frames and blew them up into lifesize formats; he took images away from museum walls and into the centre of rooms where visitors could interact with them. Not long before dying, Steichen said: "The function and mission of photography is to explain man to man and man to himself." That is the reason The Family of Man continues to capture our imaginations.